Landscapes of Healing, Landscapes of Sorrow

Deni Ruggeri, Ph,D., Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at – Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU); Executive Director and Past Chair of Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA)

When I first tried writing a reflection about the spatial implications of the COVID-19 pandemic, I became paralyzed. As a native of a small town in the province of Bergamo, the worst hit European region, I have spent the past five months in a state of anxiety. While my own community in California had yet to realize what was happening around the world, the daily phone calls with my family back home reminded me of just how dangerous this virus was and the depth of the challenges everyone there was facing. Four months after I first heard of the virus, I may now reflect and, albeit in a very unscientific and anecdotal way, learn from the experience. Rather than drawing premature conclusions as I heard so many experts do over the course of the past months, I thought I would share what I lived through in the hope that the unique stories of loved ones who have succumbed to COVID-19 can begin to suggest solutions for the future.

The setting of the events is Northern Italy is not the Italy of Rick Steve’s PBS documentaries, but the industrialized region of Bergamo and Milan, the heart of Italy’s economic engine. Nearly half of the province of Bergamo is made of rugged dolomite-like mountains and alpine valleys. In contrast, the other half is a flat agricultural plain served by two parallel rivers, the Brembo and Serio, tributaries of the river Po. Humid in the summer and cold in the winter, Bergamo is notorious for the winter fogs and poor air quality. A diffused matrix of factories and homes, the province of Bergamo is home to 1.1 million people, and a population density of 1000 people per square mile, twice the population density of Maryland, and 1/5 of the population density of Long Island. More than half of its population is employed in either manufacturing or construction. The province ranks among the most advanced economies in Europe, and its healthcare system is among the best and most advanced, making it an international hub for heart transplants and surgeries. The city houses one of Italy’s best small museums, the Accademia Carrara, and is boasts the nation’s second airport, after Rome. Known as the birthplace of Donizetti and Caravaggio, Bergamo residents identify with Atalanta, its beloved soccer team, whose success may have contributed to the spread of COVID-19, as 30,000 supporters packed the stadiums at the end of February.

COVID-19 Landscape 1: Dying in a landscape of healing

The first story is that of a family member, whom I shall call Pietro. I first met Pietro 20 years or so ago, at a family wedding, and at many other family get togethers that followed. A life-loving, intellectually curious person, he enjoyed staying active, growing food, and keeping up with politics and technology. The circumstances of his premature death are upsetting and completely avoidable. One faithful day at the end of January, Pietro left his home for a routine doctor’s visit. Accompanied by his son, he drove 15 kilometers to the regional hospital in Bergamo, one of Northern Italy’s top healthcare facilities opened in 2012. What should have been an uneventful moment turned out to be one of the most painful moments in my family’s life. Only 24 hours after entering the award-winning hospital, 78 years old Pietro had died, likely as a result of exposure to bad ventilation that let the virus spread through the space. I have thought about what may have contributed to his loss for a long time. While I have no data (other than the conversations we had as a family trying to make sense of it), as an environmental designer I have drawn a few conclusions and observations that might be useful to point out.

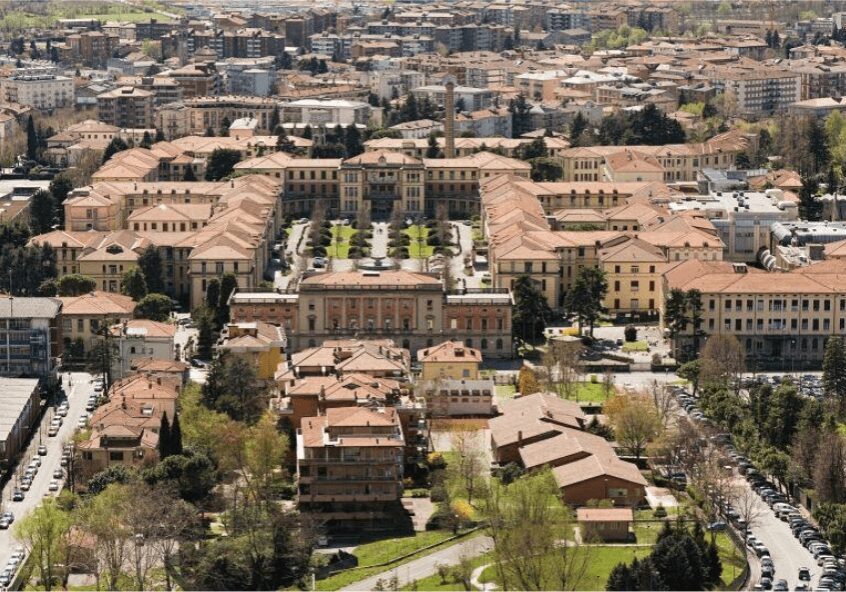

Despite being fitted with the newest bells and whistles, including exterior and interior healing landscapes, an open atrium/galleria, and views of the beautiful pre-alps, the new hospital was clearly not designed for containing the spread of a virus. Whereas the old hospital it replaced consisted of separate pavilions, distanced to avoid cross contamination and set into a lush and airy landscape (Figure 1), the new Pope John XXIII hospital—ranked by Newsweek as one of the top 50 hospital complexes in the world—feels like a huge shopping mall, complete with restaurants and espresso bars, 1200 beds, state-of-the-art technologies, and hundreds of labs and examination rooms (Figure 2). The size of a small city, the hospital attracts thousands of patients and visitors seen crisscrossing its palm-treed lobbies on any given day. Unlike its predecessor, the new hospital complex internalized the landscape and provided very limited access to open space. Knowing what we know today about the airborne spread of this disease, one cannot help but wonder whether the open and garden-like nature of the old hospital would have worked better.

Furthermore, paying for the new hospital required the closing of many small rural clinics, which could have easily been retrofitted for non-COVID-19 patients and emergencies, thus helping to limit the spread of the virus. The story of Pietro’s loss calls for the design of healthcare spaces that are adaptable and capable of quickly adjusting to accommodate new uses, or new emergencies, and for conceiving the entirety of a hospital setting, not only of its surroundings, as an affordance of health.

COVID-19 Landscape 2: Home as a landscape of sorrow

The second story is that of Laura, a younger family member who died in her home, alongside her pet dog, in a small flat buried in a busy dormitory district in the urban periphery. The city of Seriate has around 25,000 people and lies at the outskirts of Bergamo, one of Italy’s COVID-19 hotspots, not far from the hospital scene I recounted above. Unlike Pietro, this story was not that of a person caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Laura was a 52 year-old widow and mother of a 30 year-old son who had survived her husband for three decades despite an infectious disease once considered fatal. Having lost her husband to drugs, and struggling herself to live a life of addiction, Laura had learned to live alone and depend on no one but herself, responding to prejudice with self-isolation and removal from society. Over the years, she found comfort in the friendship of many, who like her, shared a story of dependence.

At an age when most people are socially connected through Facebook and Whatsapp, Laura rarely used her phone to call family members. Having been stigmatized for her past choices, she had chosen to isolate and estrange herself from her three siblings and her only son, with the exception of a few and rare visits to her parent’s home. I had last seen her in the summer of 2019, during a lighting fast visit, but she was often mentioned by relatives, who wondered how she had been.

Despite living in an apartment complex (Figure 3), Laura’s passing went unnoticed for two weeks, when a call from a neighbor to the nearby police station revealed that she had died of COVID-19 with her beloved dog. When she got sick, she thought the best solution would be to stay home and isolate herself, as so many people with pre-existing conditions were asked to do at the peak of the pandemic.

Attended by a handful of people, her funeral lasted but a few minutes, in an empty room of the City’s cemetery. No one will never know how or when she died. Overwhelmed by over 2000 COVID-19 deaths, coroners in the Province are no longer performing autopsies. Her story speaks to the anonymity, isolation, and lack of support many in our society are facing, especially those who have struggled to fit in. Laura’s death is also a reminder of the importance of bridging social capital, of taking care of all people, and not only those who share our own values and opportunities. It also speaks of the failure of contemporary city design to create environments where anyone can find support, trust, and reciprocity. I am wondering, how would design change if instead of “creating housing”, we focused on “creating communities” where people are encouraged to bridge across differences in race, economic, or life circumstances and look after and care for the most fragile and unstable, offering them words of kindness and actions of compassion.