CEC in Numbers – 1 in 9

May 12, 2021

Dear colleagues,

Do you ever think about who washes the dishes in your favorite restaurant and why? What about who picks the strawberries you buy? Migrant workers are instrumental to the developing world’s economic growth. At the same time, their earnings transform lives back in their homeland. And yet, migrant workers have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic – lack of healthcare and adequate housing are among the factors.

Today, let’s shift our focus to why the earnings of the over 272 million international migrants are important. The United Nations cites 8 facts regarding the transformative power of remittances to sustainable development worldwide:

- About 1 in 9 people globally are supported by funds sent home by migrant workers.

- What migrants send back home represents only 15% of what they earn.

- Remittances remain expensive to send.

- The money received is key in helping millions out of poverty.

- Remittances can help achieve at least these seven goals from the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (SDG): SDG 1, No Poverty; SDG 2, Zero Hunger; SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being; SDG 4, Quality Education; SDG 6, Clean Water and Sanitation; SDG 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth; and SDG 10, Reduced Inequality.

- Half of the money sent goes straight to rural areas, where the world’s poorest live.

- They are three times more important than international aid, and counting.

- The UN is working to facilitate remittances worldwide.

Below, you can read the story of a couple in Minnesota who used their earnings to build a house for their children back in Mexico.

Tasoulla Hadjiyanni, Founding Director

[email protected]

Maria and Alonso’s story – From Transbodied Spaces

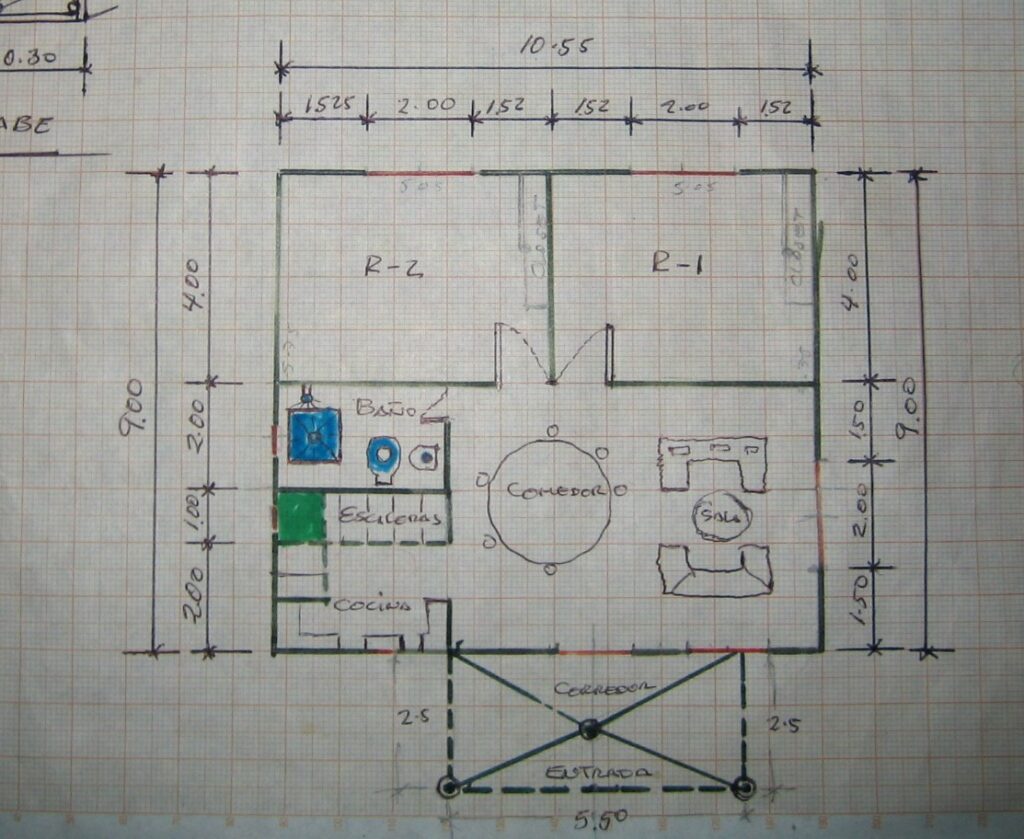

“A couple in their 40s, Maria and Alonso, have been working in rural Minnesota for 7 years……they also rented company housing that they shared with another family and a single male worker. Their savings went into building their own house in Mexico. Retaining connections to their homeland and to their children, who lived in Mexico, was what mattered. For all these years, the Mexican flag, prominently displayed in their living room, paid tribute to who they are and where they belong. Seeing their children’s smiles in photographs hanging from the walls and hearing their voices in video recordings, helped bridge the spatial divide and kept them focused on their goal:

“We are building our dream house in Mexico that we will return to within two years if all goes

according to the savings plan. This new house is already being constructed in phases, as we send

money down to the builders.“

Material possessions, in this case a flag and photographs, along with technology are mediums through which these migrant workers transbody their domestic environment into one that houses both those physically present and absent. The father built the small wooden structure the couple left behind himself. With pride, he showed us his hands, crediting them with providing shelter for his children:

“I built the house myself, with my own hands. It wasn’t that hard. I didn’t know anything about

building a house. I just figured it out. That’s what poor people do!“

Learning to build became the embodiment of a practice that would secure his children in his absence. In spite of the miles that now divide his family, Alonso is comforted to know that his children feel his presence through the physical structure he built for them. In turn, he can feel his children’s presence through the feeling he carries in his hands of creating those spaces, a feeling that nourishes his sense of fatherhood and purpose in life. He laments the fact that he is not there to help build the new house. But, as in the previous story, the absence of the parents is translated into the presence of the money they send back, which covers the building of the house. It is only through the parents’ hard work and bodily absence that the new house can take form and become in the process a transbodied space.

The old house was a small wooden structure with a palm leaf roof. It had one bedroom to sleep four people (the two parents and their two children), a small kitchen, and an outdoor patio, with a hammock and garden area. The new house speaks to their accomplishments:

“It will be a cement structure with five bedrooms and two modern bathrooms and a kitchen on two stories as well as have an outdoor patio and garden.”

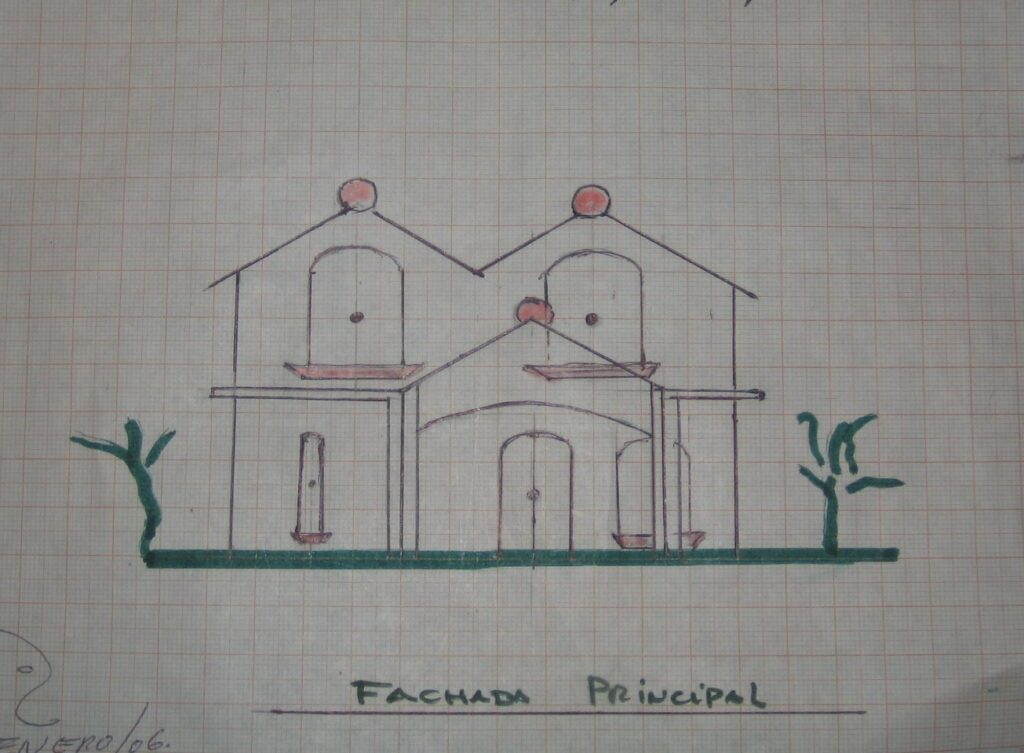

Blending the local and the global, this couple’s spatial practices created a sojourners’ spatiality, one in which the here and the there strive to become one. Unlike bodies, border crossings are inconsequential to spatial aesthetics: The house, both in its conception of necessary rooms as well as its visual presence looks American, giving hints to the couple’s years in the United States, their rising aspirations, as well as what Pader (1993) argues are “conflicting conceptual and spatial frameworks [that] become a means by which the dominant society attempts to assimilate and control subordinates” (p. 114). The sacrifices these parents and their children endured to match American spatial expectations can be construed as another form of colonialism.

In Minnesota, it was the hammock and the garden that helped them re-create a sense of home away from home. Alonso cleared the land around the company house to put up a hammock, “just like in Oaxaca.” Transbodied spaces allow for the multiplicity of ways by which bodies relax and create memories. Even when not inhabited, the hammock holds a space within it, one that resembles the womb, the space where all of what it means to be human begun (Walter, 1988). Laying in the hammock connects this couple back to their home and family in Mexico, fostering those immaterial connections that nourish a transnational belonging………

This couple’s homemaking process was also complicated by a shared spatiality. The house had three bedrooms: Maria and Alonso were in one, another couple with two children (a baby and a 4-year old) in the second one, and a single male in the third. They shared the kitchen, living room, and laundry with the other family and the bathroom with the single male. In a connected spatiality, navigating differences can be a challenge, especially among nonfamily members. Maria sometimes ate in the bedroom to be alone and away from the others. In Mexico, she said, guest bedrooms would be on the main level and the family’s rooms on top, with a physical separation that allowed for cohabitation. Transbodying spaces is a practice that is found at the intersections of connected and disconnected spatialities, one that operates on the deconstruction of spatiality into different rooms and levels, each serving different needs of the body.”

Excerpt from: Hadjiyanni, T. (2015). Transbodied spaces – The home experiences of undocumented Mexicans in Minnesota. Space and Culture, 18(1), 81-97.